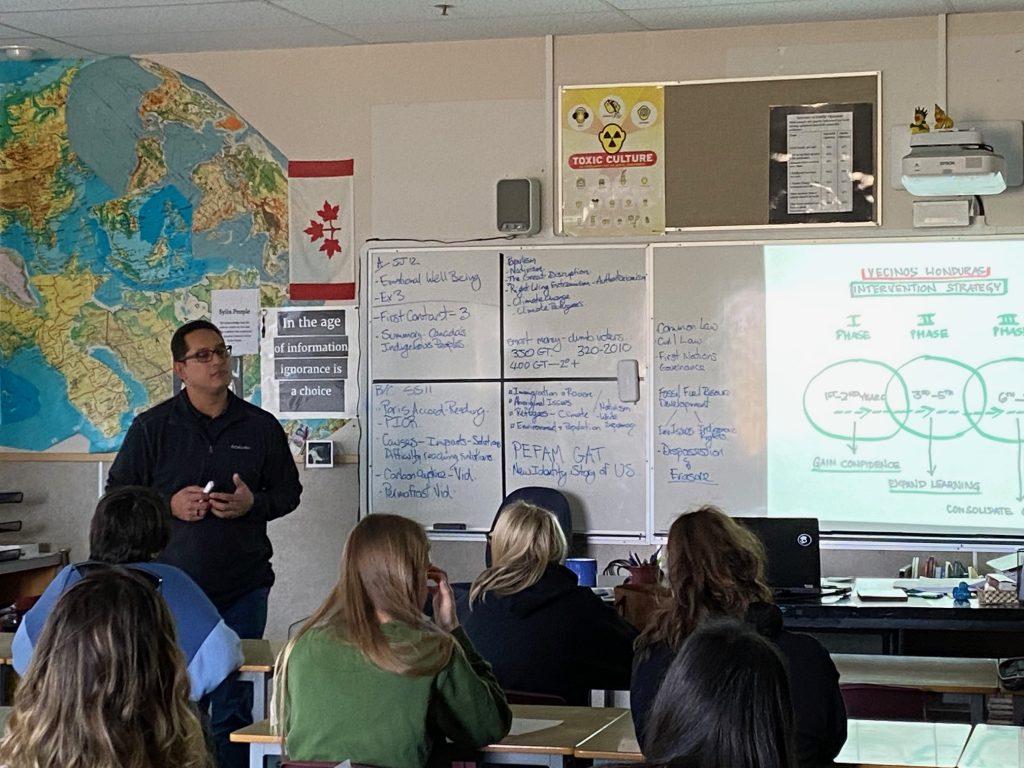

In 2020 a “call for stories” was sent out to each partner organization with hopes that people would find the time to participate. This story project was initiated to switch the narrative from having the World Neighbours Canada volunteers tell the stories of those participating in or initiating programs, to having them tell their own stories with as much or as little detail. This is one of those stories. To read more visit Stories.

Juan Armando Méndez, Honduras

My name is Juan Armando Méndez, I am a bricklayer and agroecological producer, partner of the Caja de Ahorro y Crédito Rural “Nueva Generación”. I am married to Mrs. Lucila Idiáquez with an 11-year-old daughter. I live in the community of La Libertad, Azabache Danlí El Paraíso, Honduras.

My name is Juan Armando Méndez, I am a bricklayer and agroecological producer, partner of the Caja de Ahorro y Crédito Rural “Nueva Generación”. I am married to Mrs. Lucila Idiáquez with an 11-year-old daughter. I live in the community of La Libertad, Azabache Danlí El Paraíso, Honduras.

Before Vecinos Honduras came to my community, I thought I “knew everything”, without having any idea of ”learning new things” this has motivated me more to continue learning; As a way of understanding more about the work of Vecinos Honduras, I always wondered what does it mean to Return to Earth (VH slogan)? Answering me today, “I realize that it is better to be on Earth producing, than to be with a different mind in other directions”. This new knowledge is part of the changes of a person, family and community.

I feel that my life has changed, I learned to respect nature and people, “I see them as my own person, love each other and share with others, the health of my family has changed” is also a process of unlearning some agricultural practices that were negatively affecting me emotionally and were polluting nature.

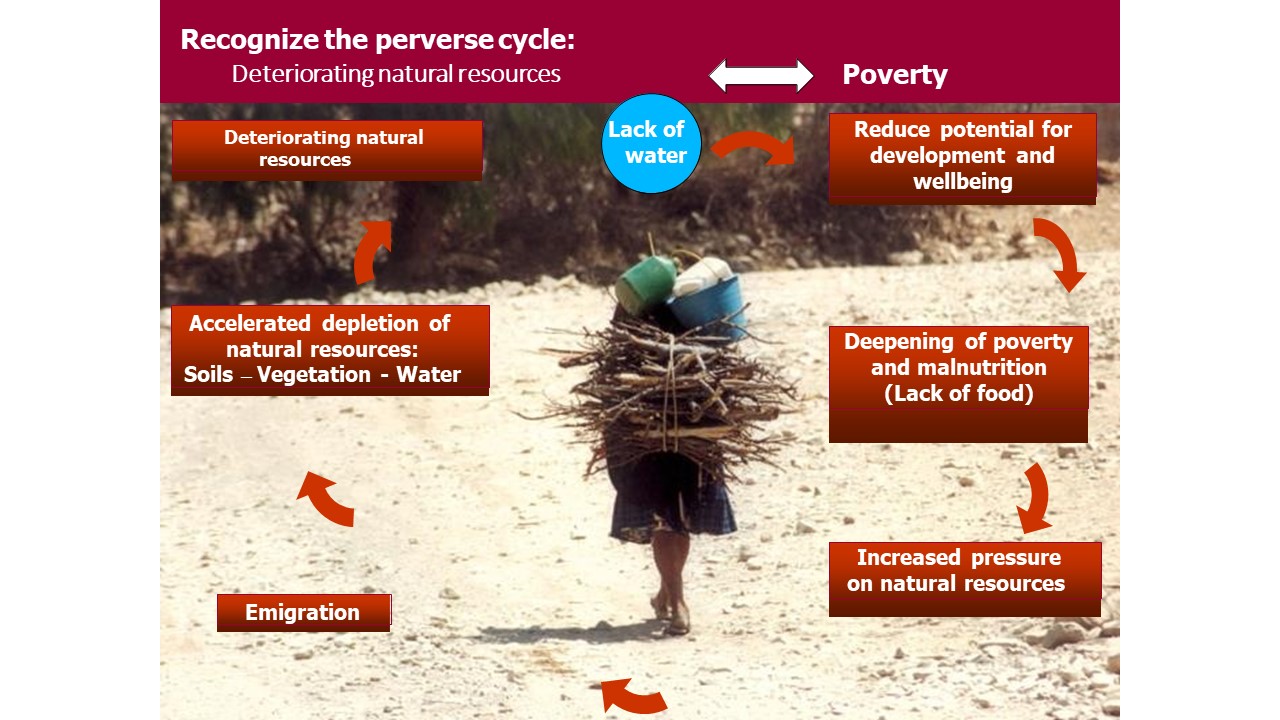

Together with my family I have a 1.4-hectare plot, diversified with local crops, its main crop is coffee. “I learned to see the plants with affection, applying organic products, taking care of the land,” and now I say, “that if there are no trees, there are no water and without water there is no life”. This philosophy is possible using organic products and stopping using chemical products. This change is not easy but not impossible, and “I have achieved it with the support of my family and Honduran neighbors”. It is already three years from beginning applying only organic products on my plot. At the beginning I lowered the agriculture production, however in this short time I increased by 1% the production from applying organic products, and I have also saved approximately $820.00 in purchase of chemical fertilizers. I feel happy with these changes for the health and economy of my family and community; “using chemicals now offends me.”

After experiencing the amino acid products (liquid) and the Bocachi fertilizer (solid) in my plot, I now share my experience, knowledge and organic product with other producers, so that they can experiment and will be convinced of the effectiveness of the product. Currently I have generated $1,200.00 from the sale of these products; next year I will invest them in expanding my growing area with 0.70 more hectares than I already have.

In addition, I am a member of a “New Generation” Rural Savings and Credit Fund. I feel motivated to be organized in my community, as “if we are not organizing it does nothing”. Being a part of this organization has given a space to market coffee production at a fair price. In the last harvest, I sold 272.15 kg of dry parchment coffee through the Rural Box, obtaining an additional profit of $168.00. “I feel happy because now I am selling the coffee well,” as before I joined this organization, I sold my product badly. Now, for every Kg I am generating an additional $1.61 because the quality of my product has improved and I am marketing through the organization, “I feel very motivated to be part of the organization.”

Together with my family we have a dream of having our coffee maca with the name “I am what I am, pure Azabache coffee”. We are already working to make it come true, it will be an option to improve and take advantage of our production, generating opportunities for families in my community.

Grateful to Vecinos Honduras and their cooperators for the support they have given us as a community, which has been used by most of the families in our community.

“I will stop neglecting myself. I will work well to succeed in my sheep-fattening and have a lot of profit.” These goals were expressed by a woman from a village in rural Burkina Faso after she had participated in an innovative project set in motion by World Neighbours Canada and our local partner organization, APDC, with funding from the Fund for Innovation and Transformation (FIT). It is one of the many inspiring testimonies we have read as our FIT-funded project recently reached its halfway point! All FIT-funded projects test innovative solutions for advancing gender equality, and empowering women and girls. These projects also have the benefit of FIT’s ongoing support as they adapt to on-the-ground challenges.

“I will stop neglecting myself. I will work well to succeed in my sheep-fattening and have a lot of profit.” These goals were expressed by a woman from a village in rural Burkina Faso after she had participated in an innovative project set in motion by World Neighbours Canada and our local partner organization, APDC, with funding from the Fund for Innovation and Transformation (FIT). It is one of the many inspiring testimonies we have read as our FIT-funded project recently reached its halfway point! All FIT-funded projects test innovative solutions for advancing gender equality, and empowering women and girls. These projects also have the benefit of FIT’s ongoing support as they adapt to on-the-ground challenges.

Though our project has only reached its halfway point, we have already seen encouraging progress that points towards the success of the novel approach we are testing! Among the highlights of the project so far is the number of women who can identify the features of a healthy sheep to purchase, and who have the support of their household members in caring for their animals. This project has allowed many women to experience a number of firsts: for the first time in their lives thirty women were able to participate in the purchase of sheep at the local cattle market. Having never before observed this process they enjoyed learning how one negotiates the terms of a purchase, or identifies a desirable sheep.

Though our project has only reached its halfway point, we have already seen encouraging progress that points towards the success of the novel approach we are testing! Among the highlights of the project so far is the number of women who can identify the features of a healthy sheep to purchase, and who have the support of their household members in caring for their animals. This project has allowed many women to experience a number of firsts: for the first time in their lives thirty women were able to participate in the purchase of sheep at the local cattle market. Having never before observed this process they enjoyed learning how one negotiates the terms of a purchase, or identifies a desirable sheep.

We have some very good news to share regarding new projects in Nepal. We have received a substantial grant from the Gay Lea Foundation, a foundation created by Gay Lea Foods (a leading Canadian co-operative owned by dairy farmers). The matching grant will enable us to undertake the building of 2-3 new piped water systems which will provide safe, accessible water to remote villages in Ramechhap district of Nepal.

We have some very good news to share regarding new projects in Nepal. We have received a substantial grant from the Gay Lea Foundation, a foundation created by Gay Lea Foods (a leading Canadian co-operative owned by dairy farmers). The matching grant will enable us to undertake the building of 2-3 new piped water systems which will provide safe, accessible water to remote villages in Ramechhap district of Nepal. My name is Juan Armando Méndez, I am a bricklayer and agroecological producer, partner of the Caja de Ahorro y Crédito Rural “Nueva Generación”. I am married to Mrs. Lucila Idiáquez with an 11-year-old daughter. I live in the community of La Libertad, Azabache Danlí El Paraíso, Honduras.

My name is Juan Armando Méndez, I am a bricklayer and agroecological producer, partner of the Caja de Ahorro y Crédito Rural “Nueva Generación”. I am married to Mrs. Lucila Idiáquez with an 11-year-old daughter. I live in the community of La Libertad, Azabache Danlí El Paraíso, Honduras.

World Neighbours Canada is pleased to share some great news! We have been selected as one of 13 organizations in Canada to receive funding from the Fund for Innovation and Transformation (FIT) in its third round of projects.

World Neighbours Canada is pleased to share some great news! We have been selected as one of 13 organizations in Canada to receive funding from the Fund for Innovation and Transformation (FIT) in its third round of projects.